The 5% of Staying Alive

For each of us, there are but a few moments in life that change everything. The story I’m about to tell changed everything about my attitude on adventure and risk-taking.

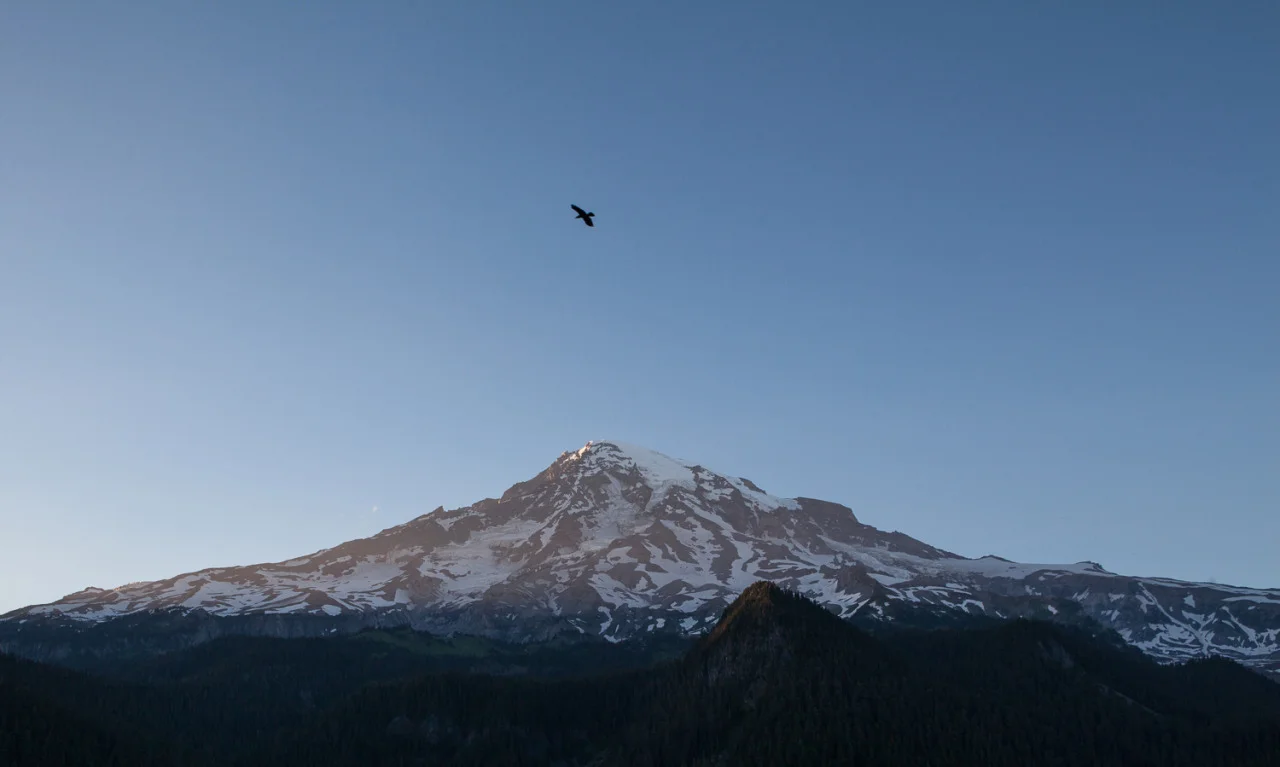

Back in 2010, my buddy Tucker and I sat down with a twelve-pack of PBR and wrote out a “tick-list” of mountains we wanted to climb. We were set on classic routes, not crazy-technical-professional-climber-type routes, but just a notch below. Committed routes on iconic mountains like Mount Rainier and Mount Hood. Each route presented a real physical challenge and serious exposure, the potential for long falls off-mountain or into a crevasse.

By this time, Tucker was a proficient mountaineer. He had spent years ski-patrolling in the winters and mountain-guiding in the summers – a true mountain man. I was a mountain poser and had the skinny jeans to prove it. I spent my days pounding away at a computer in San Francisco, and my nights reading about the places I’d rather be. Before big climbing expeditions, I’d sit in my apartment with my thousand-page mountaineering book – cramming in crucial skills and practicing rope work on my IKEA shelves.

Despite our experience gap, we both loved (and trusted) being in the mountains together, and so we started pursuing our tick-list with a special kind of fervor. At the time, finishing these climbs was a big way we were judging the success and failure of our lives.

Our tick-list went really well at first. Both of us were college swimmers, so we understood suffering and suffered well, which is about 60% of the mountaineering game. The next 35% is smarts and technical ability, and the last piece is luck – about 5%. Since you can’t control everything in life, you just hope tipping an extra dollar keeps that rock from falling on your head.

In August of 2011 we were feeling good – Mt Olympus, Mt Hood, Mt Shasta, Mt Dana, Matterhorn Peak and many lesser objectives were under our belts. We had dodged serious storms and rocks falling as fast as meteors. We had made idiotic route-finding mistakes without consequence. Things hadn’t gotten really exciting (a climber euphemism for life-threatening). We hadn’t really been tested yet.

Then Tucker called me up one day. “You down for a mission?” he asked. “Maybe, where to?” “Let’s go ice climb the U-Notch,” he said. I looked at the corner of my room – my shiny set of ice tools screamed for their virgin experience. So I took a week off work and drove six hours to the Eastern Sierra (Big Pine, CA for those of you seekers). Tucker was waiting at the trailhead, chipper as hell. It’s hard to find anyone happier in the mountains than this guy, especially while en route to “tick-off” our latest peak.

The U-Notch is a ~1,000 foot ice couloir (steep, narrow gully) that leads to the top of the North Palisade, the fourth tallest mountain in California (and one-of-twelve mountains in the state above 14,000 feet). 99% of Californians have never heard of the North Palisade and never will. It can’t be seen from any road, which is exactly why we were here.

It took us a full day of uphill hiking (and making fun of each other) to get to our high Sierra camp. That night a strange feeling began filling my body. I had felt it on a few previous climbs – the feeling of fear washing away confidence. My ice climbing skills were rudimentary, at best. I wasn’t certain in them, and I knew the mountains only rewarded certainty. I was scared but too proud to say anything, so I watched the stars turn.

The alarm’s electronic tone wailed at 2:30AM. In classic Tucker fashion, we were rolling with 12 minutes of waking. He was chipper as hell (again), and I was barely talking. The morning ice in the U-Notch was still purple when we started climbing its 45-degrees. Thunk, thunk…thunk, thunk. Two axe swings, two boot swings – we moved upward in that rhythm. The axe picks and crampons sang our thunking melody. Despite horribly-thin ice and my lack of ice climbing experience, we got up the U-Notch without much pause.

Next was the so-called “easy part” to the 14,248 foot summit – three pitches (rope-lengths) of low-5th-class rock climbing (for non-climbers, this means non-vertical). Cruiser, easy, no problem. The weather had turned, and the wind was howling, so we resorted to non-verbal rope signals. We knew what this meant but didn’t say it – we needed to get up and get out. Now! Storms don’t care, and they really don’t care at 14,000 feet.

Tucker started the first pitch and climbed out of sight. I felt the rope flick… it was my turn. I climbed about 30 feet up and hit a hard move, way harder than the route described. I was probably off-route if I had to make this move, but the weather howled at me to keep moving. To move upward, I needed to place both hands on the boulder above me, put all my weight on it, and swing my feet up the wall – essentially a swinging pull up. This was a very dynamic climbing move, but I was certain I could do it.

In this part of the Sierra, the mountains are basically giant boulders stacked on top of one another. The biggest risk was pulling the boulder off the wall when I transferred my weight. So I test-weighted the boulder, and it felt super solid. Then I went for it…….. hands up, hard pull, legs up……. OH NO!! The boulder started falling off the wall!

What I remember about this moment is hearing two very loud sounds, everything else went quiet. First, I heard the boulder – the size of a small refrigerator – tumbling down the side of the mountain, crashing and breaking down the 2,000 feet of open air beneath me. Its ruckus seemed to go on forever. I had time to think about how glad I was the boulder fell faster than I did. I had time to hope there were no climbing parties beneath us (even though I knew there weren’t). Then the second sound hit….. whoooooosh….. the sound of air rushing past my face. The sound of free fall.

My brain knew I was roped up, but somehow it had forgotten. My brain was certain I was falling 2,000 feet to my death. Tucker told me later that I was completely silent during my massive pendulum fall – no screaming, almost zen-like. And that’s the way I remember it. Zen-like. Visually, the sun was unreasonably bright, practically blinding. Life was over. I decided to enjoy the feeling of flight… it would be my last memory.

Then the harness grabbed. I hit the apex of my fall and was racing back towards the wall… WHAM. My whole right side crashed into granite. I may have been out for a few seconds, I don’t know. I just remember Tucker suddenly screaming at me. “Can you grab the wall?” he yelled. Why is he asking me this? I thought. “What!?!” I screamed back. “Grab the wall if you can… the rope is cut!” he screamed.

There are really only a few people in life you want around when shit hits the fan (i.e. you’re dangling from a partially-cut rope). Tucker is one of mine. Through a complicated series of steps I won’t describe here, he rescued me and got us to safety, all with the poise of a Buddhist monk.

“You’re so lucky you didn’t break a leg or twist a knee on that fall, or you wouldn’t be getting out of here,” Tucker said, pointing at the 100-foot wall we had to scramble to begin our down climb. “They couldn’t land a helicopter here. You would’ve spent three days on this ledge while I grabbed search and rescue,” he said. His words made me cold and hungry, and they made me think about the 5%.

Luckily, the rope was cut at the 50M mark (of a 60M rope), so we just chopped off the end and rappelled 8 or 9 times back down the U-Notch. Once we were safe, our first instinct was to discuss how could we have avoided my fall? With the weather bearing down on an easy route, I’d probably make that same decision again, especially after testing the boulder. Tucker could have placed another piece of gear to lessen my fall, but you don’t typically plan for someone to be as off-route as I was. We didn’t come up with many answers. Eventually, we decided my fall was an objective risk of climbing, just part of being in the mountains.

“I guess it all comes down to risk and reward,” Tucker said. “So this is worth the risk for you?” I asked. “Yeah, it’s worth it for me… the mountains are my life,” he said.

It wasn’t that simple for me. I completely lost my innocence on that fall. The tick-list felt more like a death-list now, and that seem like an insane reward. I had taken a big leap outside of my comfort zone – my ego had far surpassed my skills – and the North Palisade had scolded me for it. That afternoon, at 4:30PM, I fell asleep with a sunspot burned into my right retina – an exact replica of how the sun appeared when I hit the apex of my fall, the moment I thought was my last.

It took months for that fall to sink in. I didn’t climb again for 6 months, and I never approached the outdoors the same. Before that fall, Nature was yet another thing to be conquered, another place to exercise my extreme type-A personality that I never shut off. After the fall, I decided Nature was no place for type-A, it was the place to turn it off. The tick-list was over. I would climb only when I felt like it, and never because I had something to prove.

Beautiful things happened. Controlling type-A in one aspect of my life helped me control it in others. I’ve never liked being type-A, it makes me intense and competitive in an otherwise fun-loving soul. Because of one fall, I began to harness my intensity – I started having more fun, just by allowing myself to have it.

I’ve climbed a lot of hard routes since that day, but only because they made me happy. And I’ve climbed many of them with Tucker. Every time I go climbing now, I say to myself at the trailhead let’s go see what we can see. If anything feels wrong, I turn around. No second-guessing, no shame. The way I’ve come to understand adventure and risk-taking is this: if relief is the ultimate feeling when you return, you’ve gone too far. Relief is a sign that the 5% saved you, and luck refuses to be relied on.