Killing Dinner

The curves of Highway 1 tossed us left then right in our seats. We were close… the salt’s weightiness gave the air its unmistakable sea musk. Keenan talked from the front seat to me, “If for any reason you get into trouble, wrapped in kelp or stuck on something, ditch your gear. Unclip your belt and drop everything. Nothing is worth your life,” he said.

I imagined wrestling with a kelp tentacle 30 feet underwater, and thought about what I would do. From my mountaineering experience, I knew it was important to rehearse potential death scenarios (even if unlikely) than deny they existed. This would be my first dive in the chilly, churning Pacific of Big Sur.

These divine blue waters have captured the minds and cameras of tourists worldwide, but beneath the blue curtain lies an ecosystem few have ever seen. One inhabitant is particularly noteworthy – the infamous but beautiful great white shark.

Eric, our grandfather figure at 31 years of age, shared his shark wisdom, “If you see a shark, get to the bottom so it can’t get you from below. If it does come at you, poke it with your spear,” he said. “It’s a foreign object to them, and they’ll probably just swim away.” Thanks for that grandpa.

Fishy Perceptions

With all the unlikely scenarios packed away in our minds, we wet-suited up and waddled down to the beach. This required walking past our fellow campers, spear guns in hands, camo wetsuits on bodies, sweating like the land-locked sea creatures we had become.

It was May and sunny, so there were many campers, and they all noticed us… first they would stare, then smile, then utter a hearty “good luck.” These campers couldn’t hide their feelings, they were anxious for us to return with a stringer full of dead fish. I found their enthusiasm interesting.

I wondered how they would feel if, instead, we passed as hunters of big game land mammals – dressed in camo and blaze orange, holding large rifles and strapped with ammunition? Would they glean the same enjoyment if we came across camp dragging a deer carcass? It seems there should be nothing different between killing a fish and killing a deer, but it seems there is.

Mammals, we all know well. They eat grass and acorns in our yards, they bear furry, cute youth, and we try to understand and mimic their language. Fish, on the other hand, are aliens to us. They live in the water, they breathe in the water, they don’t walk, they don’t talk, and we spend very little time trying to understanding them.

In short, fish aren’t cute nor like us, and when something isn’t cute nor like us, it is easier to justify killing it.

Could I do that?

I’m going to take you away from Big Sur for a moment, so I can address something important – how do I feel about killing?

Whether it’s right or wrong to kill for food is a question you must answer. If truth exists, it always falls in the middle, so rather than attaching myself to right and wrong, I attach myself to exploring questions. These journeys always evolve my knowledge, and they usually create stories. This is my current story about killing.

Last October, I was staring down at my dinner plate when I had a vision of what happened for that pig to be there.

First, a chunk of wild land was set aside for the animal, where it was pumped with food grown on some otherwise-wild land. Then, the animal was (possibly) raised in a humane way in preparation for its last step, which is anything but humane – in some unknown factory in some unknown place, some unknown human slit that pig’s jugular for me.

By having pig on my fork, I was implicitly okay with this. But was I? I asked myself, could I do that? I wasn’t sure I could, so I decided I would find out. Killing a wild animal in a natural setting would be my way of exploring the question. There would be nothing humane about it, and I knew it would be hard for me.

Because I’ve lived on the land for 16 months, I’ve developed a respect for wild creatures that goes beyond my respect for many of my fellow humans. For in observing wild animals, you begin to understand how smart they are, how innate it is for them to live with their planet in an enduring flow.

It seems one day, we will be forced to learn their golden rule – take only what you need. I was about to take something from the land I felt I needed.

On Killing

A month after my pig-dinner realization, I went out into a frigid winter evening with a rifle, and I came back dragging a deer through the snow. I hung it in my friend’s garage and went inside to warm up.

I stood over the sink cleaning its heart, which I was about to slice, pan sear and eat. I pumped the heart a few times and watched the water flow from its right atrium to its right ventricle. I marveled at this and was deeply saddened by this – I had just killed a being which represented what I loved so much… the idea of the wild.

I was firmly connected to my food now. For the next few months, every venison meal was meaningful, and each one brought back memories from the kill – walking into the frozen dusk alone, stalking with ancestral skill that surfaced without thought, deciding to pull the trigger, dragging the deer back through the snow, tearing off its hide in one clean jerk, being with its lifeless body… cutting its meat off until 4AM in that garage.

I was not proud of these memories, but it was empowering to know I could feed myself virtually anywhere. I felt thankful for the deer’s sacrifice and spiritually linked to its life… the strength of that animal transferred to me during each cycle of nourishment.

My first kill ingrained a deep respect for the killing process. It made me want to kill more of the little meat I eat – for killing it myself would ensure the nourishment it provided was at least equal to the pain it caused me. It would be my way to ensure I wanted to keep eating meat.

It’s for this reason I bring you back to May in Big Sur and the spearfishing story.

To the bottom

I stood at the edge of the Pacific, laden with gear – wet suit, snorkel, mask, weight belt, stringer, fins, flashlight and kill knife. I asked myself, are you ready to kill?

I dunked my mask underwater, and instantly the thought of killing was erased. I was simply overwhelmed by what my retinas were returning. Beneath the blue veil of the sea shined the full color spectrum. Kelp beds burned orange in backlit sunlight, bottom dwelling plants swayed forth in deep reds and purples. Shells and coral reflected their glittery mirrors. The colors we see only at dawn and dusk on land were constantly alive under the sea.

At the surface, I started each of my drops (dives to the bottom) with a lifeless resting period. Even strapped with an 18-pound weight belt, I floated easily in my 7mm wetsuit. I calmed my mind and entered a deep-breathing trance… 8 seconds in, 4 seconds out.

My lungs told me when they were ready for an oxygen-cleanse, and when they gave the nod, I pushed my head to the bottom and kicked my feet up. Now vertical, I kicked a couple easy times to engage the weight belt, and down to the bottom I soared.

The bottom world was silent and cold and dark and moving. Not a place for an unsteady mind. The plants and fish were engaged in an eternal flow, changing directions when the waves and tides wanted them to. I added myself to this deepwater rhythm, lost in observation.

After one of my longer drops, maybe two minutes, I surfaced to Trevor’s radiant smile. “There’s a school of rockfish about 30 feet straight below me, go get one,” he said. “Do you have any advice?” I asked. “Yeah, you’re getting good long drops, but to really stay down, you need to do less,” he said. “Really, just do nothing.”

Do less, I thought and laughed in my snorkel. I hadn’t even figured out how to do that on land, and here I was in the sea, practicing that same impossible lesson.

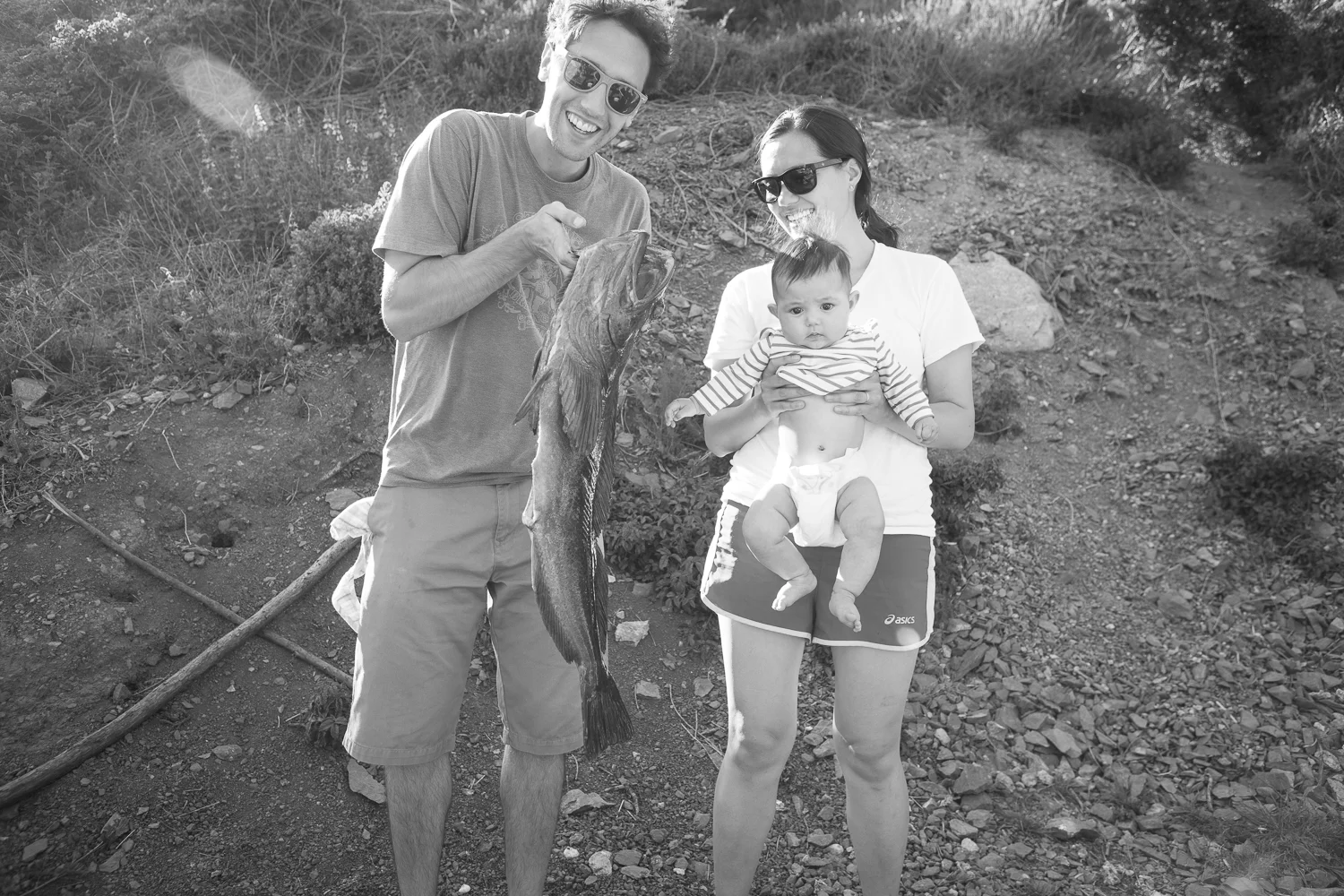

After two days of learning and many minutes of breath holding, I speared my first rockfish. It wasn’t nearly as emotional as killing the deer, which reminded me how funny my human brain was. Meanwhile, my buddies filled their stringers daily, and gray whales migrated a mere 50 feet from us.

For a week, we ate $20-per-pound fish every night, and we never tired of it. What extra we had, we gifted to our fellow campers, which attracted eager new friends with good stories.

Most days, I’m sure we burned more calories hunting the fish than they gave in return, but we were fine with this. The taste of each meal and our connection to it were things no one else could provide. After a week in Big Sur, eating the best fish from the best market would forever be ruined.